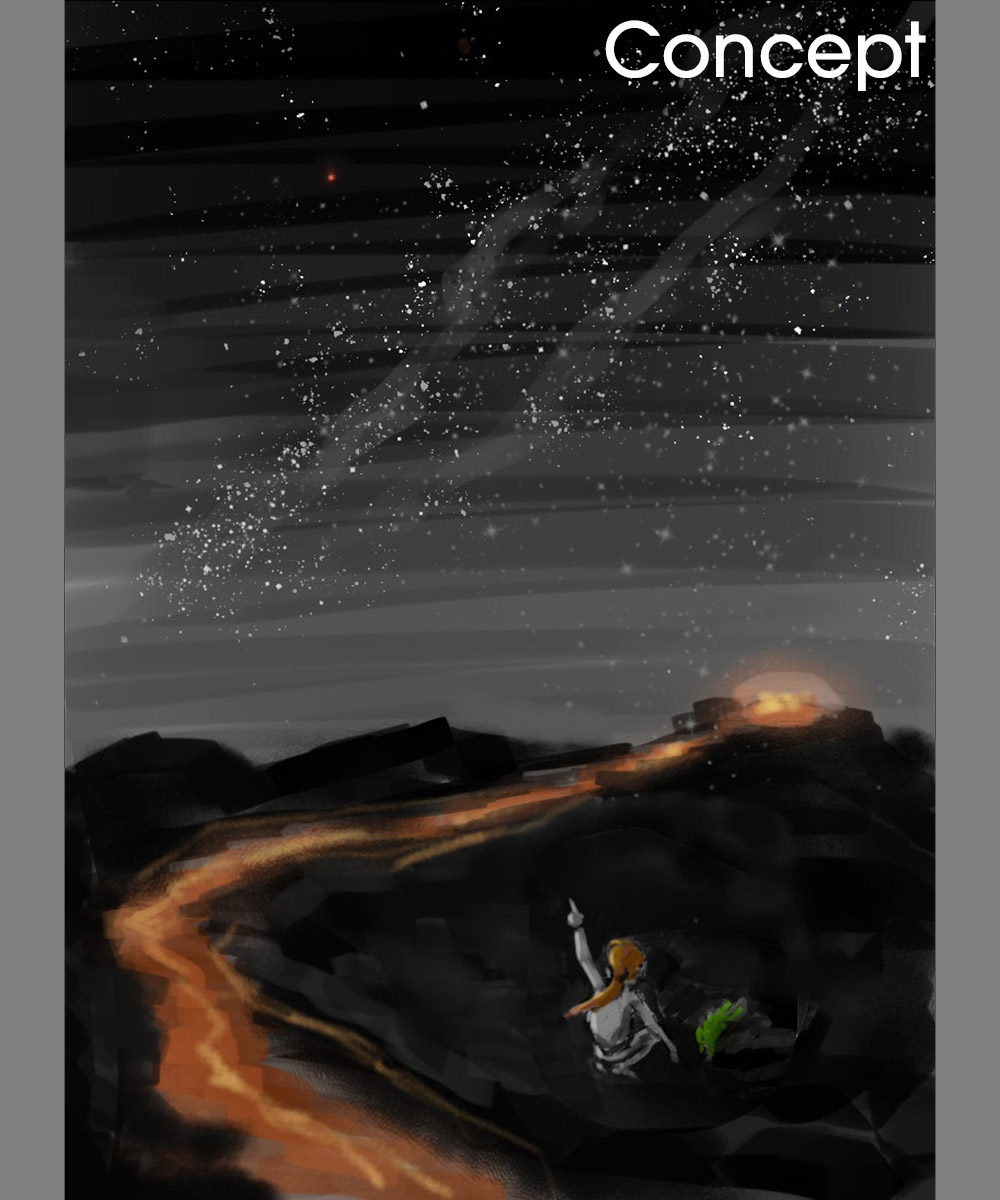

Final project for the Domestika course “Composition and Color for Creative Illustration” taught by Marcos Chin. We had to create an image to accompany a previously written text. For my text, I chose a passage from the non-fiction book The Sirens of Mars by Sarah Stewart Johnson, a planetary scientist who searches for life conditions on other planets, including Mars. In the book, she recalls a pivotal moment from her youth: a visit to Hawaii when she found a small fern sprouting in a lava field. The discovery of life in such an inhospitable place inspired her to look for life in the depths of space.

While my illustration isn’t 100% factual to what actually happened, it hopefully captures the drama of the moment and the spirit of her writing. There’s definitely a bit of Le Petit Prince mixed in my piece.

Here is the text from The Sirens of Mars, published in 2021 by Penguin Random House:

One day, when everyone was having lunch, I wandered over to check out the view from a distant ridge, where the solid lava gave way to pyroclasts and tephra. Without really noticing, I was kicking at the rocks as I stepped. I overturned a surprisingly large one with the toe of my boot, and as my eyes fell to my feet, I startled. Beneath the vaulted side of that adamantine black rock, a tiny fern grew, its defiant green tendrils trembling in the air.

There in the midst of all that shattered silence was a tiny splash of life. I crouched down to see it better.

[…]

It was just so impossibly triumphant. I couldn’t pull myself away; I looked at it for so long that the others had to come find me. I showed it to them, but I didn’t have the words to explain its beauty, its significance. I couldn’t tell them that somehow, huddled under a rock, growing against the odds, that fern stood for all of us.

Even though I couldn’t articulate it, I had an inkling then of what I know for certain now: There was something in that moment that made me become a planetary scientist. It was then, on that trip, that the idea of looking for life in the universe began to make sense to me.

I suddenly saw something I might haunt the stratosphere for, something for which I’d fall into the sea. Not fame or glory, or a sense of adventure, but a chance to discover the smallest breath in the deepest night and, in so doing, vanquish the void that lurked between human existence and all else in the cosmos. On that trip, I started to realize that, just like with Pathfinder, the process of reaching might tell me the most, might give me the chance to grasp the deepest mystery. In finding that fern, I also found something small, fragile, and worth cultivating deep inside myself.

When I got back to St. Louis from the Big Island, I tossed a hunk of the volcano into the hand of my best friend. It was part of a gathering of rocks on her desk. It was a motley collection—a pumice here, a sandstone there—but it told her that I was finding my direction. As for me, I couldn’t help but think the tableau looked a little like Ares Vallis strewn with bits of the known world. I was beginning to feel, for the first time, like a real explorer.