After I walk across the stone bridge, there’s a small cobblestoned plaza that forks into winding streets. I turn left, walking in the cramped alleys between old buildings. There are stairs, and an archway, and beyond, the buildings open up to a cemetery. It’s the only way to the old church, where they say there’s a cure for my illness.

As I cross under the archway and walk among the tombstones, I notice a lone figure. He’s dressed in an old trench coat. A wide-brimmed hat hangs over his face. Is he a gravedigger? No, this is Father Gascoigne. Like a butcher, he hacks away at something with a long axe: a body.

Like everyone else in Yharnam, he’s on the hunt. The city has fallen prey to what the remaining citizens call “the scourge of the beast”; those afflicted by this blood-borne sickness lose their humanity and turn into mindless creatures. According to the vigilante mobs that patrol the streets, the only way to stop the spread of the scourge is to hunt down those who’ve turned before they infect others.

Father Gascoigne looks up and notices me. He snarls like an animal. He’s sick, too, and is close to succumbing, but he’s still a hunter. Either I’m his prey, or he’s mine.

The battle is over in mere moments. He tears me apart. My body collapses beside a grave and disintegrates into stardust. Everything goes black.

Then I wake up.

I’m back in the town square where everything began, and everything is as it was before. I’m stuck in a dream—no, a nightmare. The only way to escape is to face my fears and conquer them.

I race through the streets past the crazed mobs that are out on the hunt. I make it to the archway, to the cemetery, to him. Again, Father Gascoigne destroys me.

Again, I wake up.

Again, I run back to him.

Again, he manhandles me.

Again, I wake up.

I don’t know how many times I’ve died, but I’m ready to give up. I can’t beat him.

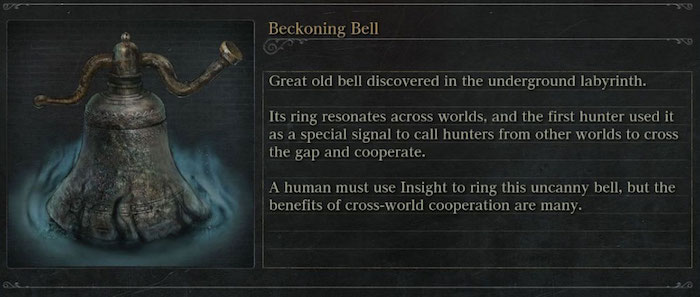

Do I have anything on me that might help me? I have a cleaver, Molotov cocktails, quicksilver bullets, a creaky music box, and an old iron bell. I look through my journal. There’s a note about this.

Hmm. I shake the bell. It rings.

A stranger from another dream hears its chime. He fades into my nightmare and greets me with a wordless bow. A friend? Sort of. It’s a real person somewhere out there who has volunteered to help anonymous strangers like me. If there are two of us, we can get past Father Gascoigne, and I can make it to the church, and I can find the cure to the sickness.

We walk into the cemetery. I run right, and the stranger runs left. Our enemy’s focus is split between us, but he’s still dangerous, bloodthirsty, relentless. He charges my new friend and, while he’s thrashing him, I hack at Father Gascoigne. He then turns to charge me, and he knocks me down, but leaves himself open for my friend to attack him.

We dance like this, back and forth, until the stranger and I hurt Father Gascoigne enough that he can’t hold onto his humanity any longer. The scourge overcomes him and he turns into a beast. He’s mindless and savage and more dangerous than ever. But the stranger seems to know exactly how to dodge Father Gascoigne’s swipes and lunges. The stranger knows exactly when to fight back and when to run. I follow his lead. We chip away at Father Gascoigne until, with a final slash, I put the beast down.

The stranger bows before turning to stardust and fading away. Beside Father Gascoigne, I find a key that opens the gate leading to the old church. Finally.

Bloodborne is one of my favourite games of recent years. It’s terrifying, difficult, and often opaque about what’s actually happening in the story, events that are awesome, dreadful and stupefying.

Progress requires effort, and a lot of it, because the odds are against you. The enemies are countless and merciless, and death (yours) is as frequent as breath. To earn fleeting moments of success and understanding, you need what psychologists call grit, resilience, or optimism: the determined pursuit of a goal despite failure or adversity. “Fall seven times, stand up eight,” as the Japanese proverb goes. As a player, you have to commit like a monk to the cycle of death and rebirth you’ll experience, and to all the frustration and learning that comes with it. The issue is what will break first: the game’s challenges or your resolve. Will you keep trying, or will you let go of your humanity and “rage-quit” like a beast?

If you ever feel such forced growth is too much for you to bear, you can give up. You can put the controller down and walk away. You can play something light like Candy Crush. But every time you consider throwing the game disc out the window, you remember the beasts and the irrational, pitchfork-wielding mobs who stumble through Yharnam looking for someone to blame. If you give up, you’ll become one of them. You don’t want to be one of the failures, the weak, the broken, the sheep. You want to be a game-difficulty hipster. You want to be strong, resilient, determined, heroic. You want revenge against the inhuman thing that killed you fifty times before, because every hard-earned victory is a religious experience. So you try again.

There are times when the odds seem too great. When that happens, you can reach out to other players and hope someone will jump into your world and help you. Admitting your weakness isn’t failure; the game designers put the Beckoning Bell in the game intentionally. When you’re alone, you’re outmatched. That’s when you need better tools, even if those tools are carried by other people.

One day, you’ll be one of those other people and you’ll help someone else along. You’ll be the lifeline that strangers hold on to. You’ll hear their bell and answer their call. And the more you help them, the stronger your character will become—in every sense of the word.

There isn’t any moment in Bloodborne when anyone takes you aside and gives you a pep talk about never giving up. There’s no sitcom-dad moment, no “very special episode”.

If anything, the people in the story are snide. They taunt you into quitting, and laugh at your mistakes. They hide truths and secrets, then mock you in their Cockney accents for your lack of knowledge. Even the real players you occasionally meet can only communicate with you through their characters’ body language.

You have to unravel the world’s mysteries yourself, just as you might have to while travelling in a foreign country without a guidebook. You’re the one who has to grow. You’re forced to manage your wild emotions and embody the resilience and cooperation the game indirectly preaches. You know other players have finished this game, so there must be a way. Maybe you need their help, or maybe you can figure it out on your own. Either way, you keep trying. Resilience is the greatest weapon you have.

As I played Bloodborne, I thought about how easy it was to summon help in facing the game’s greatest challenges. Thinking about how the game shares, experientially, its lesson about resilience in the face of hopelessness, I thought about what other lessons it might have to offer.

I even wondered, a bit childishly, why we can’t have a Beckoning Bell in real life. Where is the lifeline we can call when things are beyond human control? Because I’m a (conflicted) spiritual person, my mind drifted to prayer.

At least in my own tradition, Islam, prayer is supposed to be how we relate to the divine. It’s the prism through which we see the light, however fractured. And it is fractured. My spiritual life is filled with frustrating contradictions and unsatisfying rationalizations. Like a stubborn, resilient Bloodborne player, though, I keep working with those frustrations. I know what I’ll become if I give up.

The truth is I don’t know how prayer works. Whether I use the sacred Arabic verses or my own impromptu English ones, I say words, and they echo through my mind or through the realms of the universe, but do they have an effect? Does anyone hear? I’m meant to believe there’s a divine presence out there that hears my pleas: God alters the geometry and physics of the world to resolve my problems; angels fly down to shield me from drunk drivers. It’s all invisible, though.

As I write this, I feel very self-conscious about how it sounds. The whole thing feels silly. There’s a reason many religious people don’t like talking about the nitty-gritty of their faith. After all, I pronounce ancient words and read from old books the way wizards do in movies, and whether it’s my doing or a response from the divine, I expect something supernatural will happen. This is what I literally believe. I laugh at The Secret, but what I do isn’t functionally different. It’s just older.

Sometimes people talk about prayer (or The Secret) the way they talk about deadlifting or constipation: you just have to do it hard enough. I know, though, that prayer doesn’t work like that. Whether people pray the Montreal Canadiens will win their twenty-fifth Stanley Cup, or they pray they’ll reach the Turkish border and escape ISIS death squads, those prayers may be answered—but then again they may not be.

For prayer to work, it would need to be consistent, the same way that, when people call 911, an ambulance shows up. Even Bloodborne’s Beckoning Bell is more clear-cut. There isn’t always a stranger to help you, and summoning one doesn’t guarantee you’ll succeed, but at least the whole system is black and white.

What if we lived in a world where we could pray, we could ring our own Beckoning Bell, and divine help was obvious and accessible? What if we could rely on prayer the way we rely on 911? Wouldn’t more people believe in God, then? Obviously, reality couldn’t function as we currently know it, especially if people prayed for mutually exclusive things. But God (being God) could make it work, and, as a result, we’d have a more direct and rich relationship with the force behind creation.

I suppose it’s a moot point.

In Bloodborne, you’re on a journey to unravel a mystery about the scourge of the beast—what caused it and how to cure it. There are others on the same path; you encounter these characters during your adventure. When you meet them, though, they aren’t full of aloof wisdom about the beastly nature inside the human heart. No, they’ve torn their eyes out and gone mad after pondering unfathomable questions or learning things humans were never meant to learn.

Back in the real world, we settle for unsatisfying axioms like “God works in mysterious ways.” It’s the equivalent of a parent telling their kids maybe they’ll go to the toy store later. It’s stalling, which is easier than putting up with an argument. And here I am, like a five-year-old: “But why?” and “Is it later yet?”

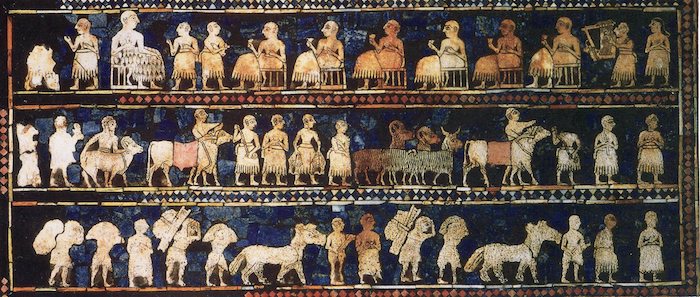

There was a time when ritual and ceremony felt more effective, when the causality wasn’t so mysterious. While spiritual behaviour goes back hundreds of thousands of years in our prehistoric past, I’m thinking of the way we acted in early civilizations like Sumer and Babylon. A priest would climb atop a ziggurat at the start of every new year to perform a sacrifice. The rituals they performed weren’t meant for private comfort, but to renew the covenant with the gods for another year. In doing so, they would keep the fragile accomplishment of civilization afloat among a sea of cosmic forces, many of which could be felt directly in the unpredictable natural world. Ritual was about direct material benefit. If people didn’t perform the rituals, the gods would take everything away with a drought, an earthquake, a storm, an eruption.

We don’t live in such a superstitious society anymore. Like the rest of our brain, our spirituality has evolved since its prehistoric roots. So why keep up the pretence? Why keep praying if it’s all a misplaced reaction to the baffling inconsistencies of life? Why bother if no dream-stranger will materialize in front of us and help us?

For the same reason we play games: praying feels good.

Sure, it’s not logical to believe in magic. But when it comes right down to it, it feels good to imagine magic exists.

I know that sounds irrational. It was Sigmund Freud who theorized that the belief in God was a vestigial childhood need for an all-powerful father figure. Freud thought we were all immature and that, like children, we all desperately wanted a hug. Even though he sometimes used mythic metaphors to explain his ideas, he was like other thinkers of the time. He had a materialist world view; abstract ideas required material proof to be considered valid. Emotions were infantile neuroses. Modern people were supposed to be dispassionate and stoic. They were supposed to be beings of pure will who could weather any storm alone, like a Bloodborne player who refuses to call for help.

Well, for one thing, most of Freud’s wacky ideas have been left behind by psychologists.

And even if they hadn’t been left behind, so what if we all just want a hug? So what if some of us cry at Pixar movies? Is that so wrong? You try watching the first five minutes of Finding Dory and not crying!

I’m not hyper-evolved enough to have moved beyond that. I’m not saying I’m going to start sending mystical chain letters, or teach kids that Jesus rode dinosaurs, or whatever. I’ve had a strong love of science and history since I was an immature child. Yet I also think it’s up to us to create the richness we want from the universe, and to approach life with playfulness. And that playful part of me wants to call out in the middle of the night and hope someone is listening. That part of me still wants to hope. Hope gets us through the darkest storms.

In Islam, we end our prayers on our knees. We cup our hands together and we whisper to God. We fill our hands with hope. Then we stand up. It’s not about the words, the logic, or even the result. It’s about the feeling, the act, the intention.

But I still wish I had a bell.

(Images 1–4 © Sony Interactive Entertainment LLC. Image 1 by SP17FIRE. Image 2 by Gosu Noob. Image 5 by Alma E. Guinness.)

(This post also appears on Medium.)